Type species: Sphinx pinastri Linnaeus, 1758, by subsequent designation by Grote, 1873, Bull. Buffalo Soc. nat. Sci. 1: 27.

An Old World genus predominant in the Eastern Palaearctic region, but with two/three species occurring in the western Palaearctic. Unpublished phylogenomic analyses confirm that to prevent paraphyly of Sphinx, the genus Hyloicus must be accepted as valid (as asserted by Zolotuhin & Yevdoshenko, 2019). The reasons for splitting Sphinx and Hyloicus are outlined by Haxaire, Melichar & Rougerie (2023).

OVUM: Ovoid, usually pale green/yellow. Large.

IMAGO: Hindwing with two dark submarginal bands. Proboscis approximately equal to length of body, and functional. Antenna of even thickness in both sexes and with a very weak terminal hook. Eye small and lashed. Abdomen with grey/black and white 'rib' markings. Forewings cryptic grey with dark streaks. Hindtibia with two pairs of spurs, the proximal much longer than the distal. Distinguished from other Sphingidae (except Sphinx) by the spined foretibia and lack of a pulvillus.

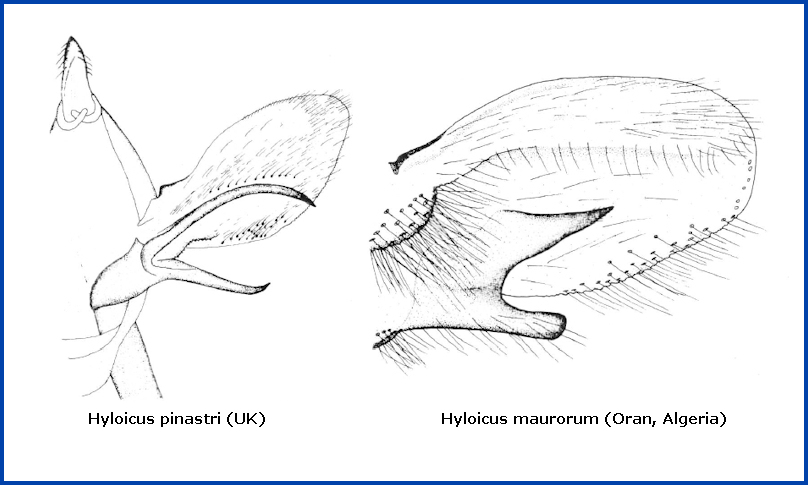

Genitalia. According to Hodges (1971), '...the male and female genitalia seem to offer fairly consistent points of difference to separate the species from those of other genera...The male genitalia are somewhat diverse; however...the saccus is relatively broad with the apex rounded; the saccular margin is heavily sclerotized, and the apex may be either bilobate or with a single lobe; the gnathos is broadly rounded to slightly spatulate; the uncus is broad at the base, tapering to a point, in some there is a ventral development; the phallus is unarmed, and one side tends to project beyond the opening for the vesica. In the female genitalia, the genital plate, consisting of the joined lamellae ante- and postvaginalis, often is a broad, heavily sclerotized unit; the ostium bursae is often centred on this plate; the base of the ductus bursae may be heavily sclerotized or not; the corpus bursae is membranous, and a slender, U-shaped signum with a series of short, pointed projections is present'.

LARVA: Head slightly narrowed above, almost round, never pyramidal; body cylindrical and elongate. Colour usually some shade of green or grey with brown shading dorsally; typically sphingiform. Body with broken longitudinal pale streaks and concentric dark rings. Unlike Sphinx body never with seven oblique lateral streaks of white, or white and a dark colour. In the final instar rarely granulose. Horn erect, dark, thin, and slightly curved and granulose in the final instar.

PUPA: Glossy reddish brown, with a small, free proboscis lying parallel to the body in some, or replaced by a small knob in others.

HOSTPLANT FAMILIES: Only conifers in the family Pinaceae.

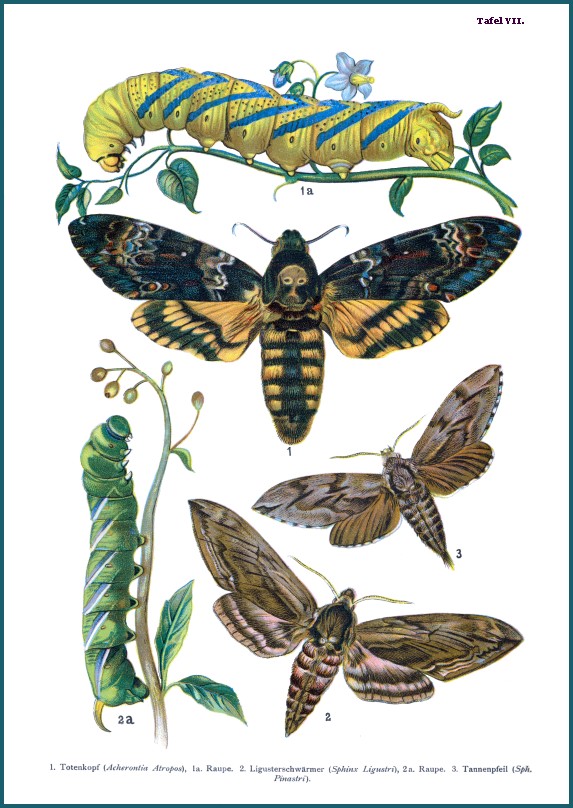

UK: Pine Hawkmoth, F: Sphinx du Pin, D: Kiefernschwärmer; Tannenpfeil, RUS: sosnovy brazhnik, S: Tall-Svärmare, NL: Dennenpijlstaart, CZ: Lišaj borový, H: fenyőszender, E: esfinge del pino, PL: Zawisak borowiec, FIN: Mäntykiitäjä, I: sfinge del pino, HR: borov ljiljak, DK: Fyrresværmer, N: Furusvermer, EST: Männisuru.

Sphinx pinastri Linnaeus, 1758, Syst. Nat. (Edn 10) 1: 492.Type locality: Unspecified [Europe].

(Taxonomic notes. (i) Hyloicus pinastri euxinus cannot be considered a distinct subspecies as the genitalic differences used to separate it from Hyloicus pinastri are not marked; in these respects it differs as little from the nominate race as do 'subsp.' cenisius Jordan or 'subsp.' medialis Jordan, which are synonymized with pinastri (for the reasons given below).

(ii) Due to consistent differences between the male genitalia and every early stage of Hyloicus pinastri and Hyloicus maurorum Jordan, 1931, the latter must now be considered a distinct species. Eitschberger et al. (1989) raised Hyloicus maurorum to specific rank but gave no reasons for doing so. Although Hyloicus maurorum and Hyloicus pinastri (Linnaeus, 1758) interbreed in central and eastern France, and have formed natural intermediate populations, this hybrid zone is narrow and stable. It is probable that Hyloicus maurorum evolved for some time in isolation in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula and that only since the end of the last ice age has it come into contact again with Hyloicus pinastri, which appears to have retreated to south-east Europe during that ice age. Kernbach (1958) reached similar conclusions. Post-glacial zones of secondary contact and hybridization between once isolated sister species are known as suture zones, and have been reported for a variety of taxa in many biomes (Barrowclough et al., 2019; Ipekdal et al., 2020; Moritz et al., 2009; Portnoy & Gold, 2012).

(iii) The Oriental Hyloicus morio Rothschild & Jordan, 1903, Hyloicus caligineus Butler, 1877, Hyloicus brunnescens (Mell, 1922), Hyloicus bhutana (Brechlin, 2015) and Hyloicus oberthueri Rothschild & Jordan, 1903, previously considered subspecies of Hyloicus pinastri, are most certainly separate species, with distinct differences in behaviour and genitalia (Derzhavets, 1979b; Litvinchuk, 1986; Owada & Kogi, 1992; Brechlin, 2015).)

In this work the following classification and synonymies have been adopted for the Hyloicus pinastri 'complex', including those from eastern Asia:

The subspecies marked with an asterisk (*) appear to be the result of hybridization between several races and subspecies which evolved in separate refugia during the last ice age, a conclusion also reached by Kernbach (1958).

Hyloicus morio Rothschild & Jordan, 1903 is now recognized as a species distinct from Hyloicus pinastri. Subsp. arestus Jordan, 1931 inhabits central and eastern Russia (Zolotarenko, Petrova & Shiryaev, 1978), Mongolia, north-eastern China (Chu & Wang, 1980) and Korea (Owada & Kogi, 1992); subsp. morio occurs on Hokkaido, and central and northern Honshu, Japan. (Confusingly, Hyloicus morio was incorrectly reinstated as a subspecies of Hyloicus pinastri by Inoue in Inoue et al. (1982: 318).). According to Litvinchuk (1986), Hyloicus morio mates only during the morning. This differs from the behaviour of Hyloicus pinastri and, if confirmed by further studies, may explain how these two species remain reproductively isolated. A similar mechanism keeps Hyles euphorbiae (Linnaeus, 1758) and Hyles tithymali (Boisduval, 1834) isolated.

The very similar Hyloicus caligineus, Hyloicus brunnescens, Hyloicus bhutana and Hyloicus oberthueri are restricted to temperate eastern Asia. In fact, all eight species are similar in appearance, both as adults and larvae.

[Further details on this species, as well as photos of all stages, can be found on Lepiforum.]

Holarctic; western Palaearctic region. Pleistocene refuge: Polycentric -- Pontomediterranean subsection of the Mediterranean refuge, as well as the Caspian refuge.

Wingspan: 70--96mm. Shows little resemblance to any other western Palaearctic hawkmoth, except to some extreme forms of Sphinx ligustri Linnaeus, 1758. Ground colour very variable, ranging from dark brown (f. brunnea Spuler) to cream (f. albescens Cockayne). The normal grey colour may be of almost any shade, while the dark grey, discal bands on the forewing may be absent, or so heavy as to coalesce, forming one solid band (f. semilugens Andreas).

In the male genitalia, the upper harpe branch is much longer than the lower, more or less heavily curved, almost always cylindrical in its apical half and with only rudimentary prongs (see below left), and thus very similar to those of Hyloicus corsica. The apical apophysis and phallus are long. This is markedly different from that of Hyloicus maurorum (see below right).

Found in open or mixed pine forests, especially on dry heaths and wooded steppe (Izerskiy, 1999); also in mountain conifer forests up to 1600m in the Alps (Forster & Wohlfahrt, 1960), but at around 2000m in the Lebanon (Zerny, 1933; Ellison & Wiltshire, 1939).

Rests by day on a solid surface, usually the trunk of a pine tree, where it is extremely well camouflaged. Most often, single or isolated groups of trees are selected and it is in such situations that mating pairs are often found, for females are reluctant to fly until paired and remain on the trunk near where they emerged. Although some will separate in mid-afternoon, pairs normally remain in copula until dusk, when males fly off to feed, and possibly mate a second time, while females commence egg laying. Most sweet-smelling flowers, especially Lonicera, are avidly visited, with no time preference being shown. Both sexes are regularly attracted to light.

According to Izerskiy (1999), females tend to be active between 23.00h and 01.10h, males between 23.40h and 02.50h. This is in distinct contrast to the related eastern species, Hyloicus morio arestus, which is active at dawn.

Univoltine; in northern latitudes and Siberia, June or even July; farther south bivoltine, during May/June, and again in August as a partial to full second brood. In the southern Urals, from late May until early July (Nupponen & Fibiger, 2002). In southern Turkey (Adana Province), from late May until late June (Feza Doganlar, pers. comm.).

OVUM: Oval and slightly dorso-ventrally flattened (2.00 x 1.5mm); shiny pale yellow at first, changing to reddish yellow. Each female lays approximately 100 eggs, usually singly in close proximity to each other, on the needles or young twigs of isolated or small groups of trees. Development takes 6--9 days at 19--22°C, 14--20 days under cooler conditions. Just before hatching the dark head of the larva becomes visible through the now transparent shell.

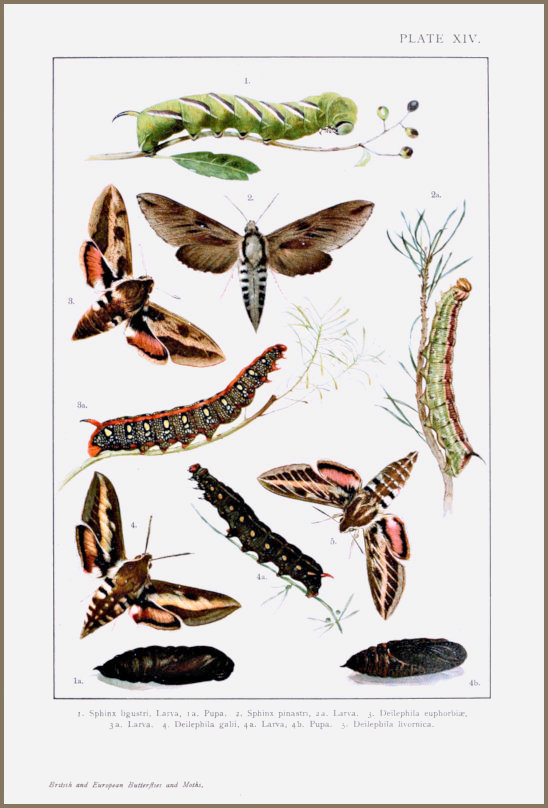

LARVA: Full-fed 75--80mm. Dimorphic: predominantly green or brown.

On hatching, the larva consumes part of its eggshell. At this stage it is approximately 5mm long and dull yellow, with a disproportionately large head marked with brown, and a dark, forked horn. With feeding, the body colour changes to green and, after the first moult, six longitudinal creamy yellow lines appear. Still disproportionately large, the head is a paler green than the body, and has dark cheeks. During this stage, the larva sits lengthways on a pine needle, with which it blends very well. Apart from the longitudinal lines becoming broader and the horn and legs acquiring a reddish tint, little change takes place to its appearance over the next two moults.

Fully grown, larvae may be either leaf-green with a marked reddish-brown dorsal band and three broken cream or white longitudinal lateral stripes, or mainly greyish-brown, blending well with surrounding twigs. In both colour forms the whole body, which is slender and of even thickness, has dark, sunken, encircling lines, apparently dividing it up into narrow rings behind a large, prominent, ochreous-colored, black-lined head and shield. The body is smooth, but not glossy, unlike the head, underside, legs and shield. However, an oily appearance extends over the entire body as the larva darkens prior to pupation.

Mature larvae can easily be told apart from those of Hyloicus morio arestus Jordan, 1931 in that in the latter the dark dorsal band is more well defined, purple-brown (and not reddish-brown as in H. pinastri), and is bordered on either side with a greyish-white stripe. The basic green body colour of Hyloicus morio arestus also has a more emerald hue than does that of H. pinastri.

Initially, feeding consists of nibbling at the surface of a needle but, with increasing size, whole needles are consumed, being grasped between the legs and eaten from the tip to the base; older needles are preferred to younger ones. It is a sluggish diurnal feeder, never moving more than necessary, and comparatively little plant matter is consumed during this 4--8 week period. However, just before pupation, the larva becomes very restless and, after descending from the hostplant, it will wander some distance in search of a pupation site.

In Finland, larvae prefer short and weathered pines (Pinus sylvestris), especially ones growing beside bogs, marshes, sandy areas or other open places. Larvae live in the top branches and feeding sites are easy to spot later in the summer as the terminal shoots are usually eaten bare (Jaakko Pohjoismaki, pers. comm.).

Feeds during July, August and September in the north, and June/July and September/October in southern regions. At times, larvae can be so abundant as to constitute a pest (Selys-Longchamps, 1857; Gninenko, 1998).

Major Hostplants. Various species of Pinus (especially Pinus sylvestris) and Picea (especially in the Alps); Picea abies is a favourite in Poland (Garbowski, 1892). Picea obovata is the main secondary host in Siberia (Izerskiy, 1999). In the Republic of Georgia on Pinus nigra, Pinus sylvestris var. hamata [syn. Pinus sosnowskyi] and Pinus brutia var. eldarica [syn. Pinus eldarica] (Didmanidze, 2005).

Minor Hostplants. Larix decidua (northern and central Europe), Cedrus (southern Europe) and Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas Fir).

PUPA: 35--40mm. Very similar to that of Sphinx ligustri and usually formed under moss or the needle mat found at the base of trees. The overwintering stage; may overwinter twice.

Ichneumonidae: Amblyjoppa proteus (Christ, 1791), Apechthis compunctor (Linnaeus, 1758), Apechthis rufata (Gmelin, 1790), Aphanistes bellicosus (Wesmael, 1849), Aphanistes gliscens (Hartig, 1838) [syn. Aphanistes armatus (Wesmael, 1849)], Aphanistes klugii (Hartig, 1838) [syn. Aphanistes megasoma Heinrich, 1949], Aphanistes ruficornis (Gravenhorst, 1829), Coelichneumon deliratorius (Linnaeus, 1758), Coelichneumon sinister (Wesmael, 1848), Cratichneumon luteiventris (Gravenhorst, 1820), Cratichneumon sicarius (Gravenhorst, 1829), Diphyus palliatorius (Gravenhorst, 1829), Heteropelma amictum (Fabricius, 1775), Heteropelma calcator (Wesmael, 1849), Metopius dentatus (Fabricius, 1779), Protichneumon fusorius (Linnaeus, 1761), Protichneumon pisorius (Linnaeus, 1758), Therion circumflexum (Linnaeus, 1758); Pteromalidae: Erdoesina alboannulata (Ratzeburg, 1852); Encyrtidae: Ooencyrtus pityocampae (Mercet, 1921) (an egg-parasite); Tachinidae: Campylocheta inepta (Meigen, 1824), Compsilura concinnata (Meigen, 1824), Drino (Zygobothria) atropivora (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830), Drino inconspicua (Meigen, 1830), Drino vicina (Zetterstedt, 1849), Exorista larvarum (Linnaeus, 1758), Nemoraea pellucida (Meigen, 1824), Phryxe erythrostoma (Hartig, 1838), Phryxe nemea (Meigen, 1824), Phryxe vulgaris (Fallén, 1810), Tachina grossa (Linnaeus, 1758), Winthemia cruentata (Rondani, 1859), Zenillia dolosa (Meigen, 1824).

Phryxe erythrostoma is a specific parasitoid of Hyloicus pinastri, with as many as eighteen examples being recorded from one host pupa.

Attacked by the fungus Cordyceps militaris in Poland (Zablocka, 1929), as well as Cordyceps sphingum (Garbowski, 1892).

From Europe (except Iberia, Ireland, northern Scandinavia and Arctic Russia) and western Siberia (Eversmann, 1844; Zolotarenko, Petrova & Shiryaev, 1978) south to the southern Ukraine/Crimea (Efetov & Savchuk, 2012; Khalaim, 2022), Moldova (Tugulea & Tugulea, 2020), Daghestan (Didmanidze, Petrov & Zolotuhin, 2013), the Republic of Georgia and Armenia (Didmanidze, Petrov & Zolotuhin, 2013; Streltzov et al., 2022; Roma Alekseev, iNaturalist 2024), the Caucasus (Derzhavets, 1979b; Abdurahmanov, 1999), Azerbaijan (Snegovaya & Petrov, 2021) and southern Turkey (Daniel, 1932; Daniel, 1939; Kernbach, 1958; Ayberk & Akkuzu, 2005; de Freina, 2012; Okyar, 2012; Kemal & Koçak, 2018b; Koçak & Kemal, 2018), Lebanon (Zerny, 1933; Ellison & Wiltshire, 1939) and northern Israel (Müller et al., 2005b).

In western Europe it is found east and north of central France (Pittaway, 1983). There are some local populations in central-southern France showing small differences in genitalia which were separated into individual subspecies by Jordan (1931), but this is unwarranted. Also found on the island of Pantelleria, Sicily (Corso, 2011), Croatia (Koren & aić, 2023), Bulgaria (Karisch, 1990; Krpač et al., 2019) northern and central Greece, in the northern Aegean on the islands of Thassos (Koutsaftikis, 1970) and Samos (Fritsch, Stangelmeier, Top-Jensen & Bech, 2014), and on the island of Rhodes (Roger Perkins, pers. comm 2021).

In eastern european Russia the distribution of this species now overlaps with that of Hyloicus morio arestus in the southern Urals, especially around Chelyabinsk and Yekaterinburg. In this area both species are quite common in dry pine and mixed forests. Hyloicus pinastri has also been recorded as far north as Arkhangelsk Oblast (Kozlov, Kullberg & Zverev, 2014) and Pechora (Tatarinov, Sedykh & Dolgin, 2003).

Duncan (1836) regarded this species as being rare in Britain, with it occurring with certainty only around Esher, Surrey; Drury (1837) stated that Hyloicus pinastri was only a very rare vagrant. With the extensive cultivation of pine plantations over the last 100 years, this immigrant has become well established and has spread over most of southern England where both commercial and ornamental pine trees occur. A good account of its early status in England is given by South (1907).

The situation in France appears to have changed over the last 20 years, with this species having been displaced by Hyloicus maurorum from many southern areas. True Hyloicus pinastri can now only be found north of Chateauroux, in the Alps and Var. Populations around Toulon are clearly intermediate hybrids (J. Haxaire & J.-M. Bompar, pers. comm.).

The population on Corsica (Bretherton & de Worms, 1963) has been classified at various times as Hyloicus pinastri or Hyloicus maurorum (Haxaire, 2009; Haxaire, pers. comm 2018; Haxaire, 2019). However, this population has now been reclassified as Hyloicus corsica Haxaire, Melichar & Rougerie, 2023.

Extra-limital range. None.

Hyloicus pinastri has been recorded from certain parts of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, and specimens have been found in the eastern U.S.A. (Hodges, 1971). Whether the former are native or escapees is not known. It is possible that they are the last remnants of the original North American population of this species which went on to colonize the Palaearctic, but this, of course, is pure speculation. [See Dvořák, 2023, for a discussion on this.]

None.

Return to species list

Return to species list