Type species: Sphinx ligustri Linnaeus, 1758.

A large genus found mainly in the New World, especially in the Nearctic region, but with two species occurring in the Palaearctic, one of which reaches the western part of the region. Unpublished phylogenomic analyses confirm that to prevent paraphyly of Sphinx, the genus Hyloicus (previously included within Sphinx) must be accepted as valid (as asserted by Zolotuhin & Yevdoshenko, 2019) and separate from Sphinx. The reasons for splitting Sphinx and Hyloicus are outlined by Haxaire, Melichar & Rougerie (2023).

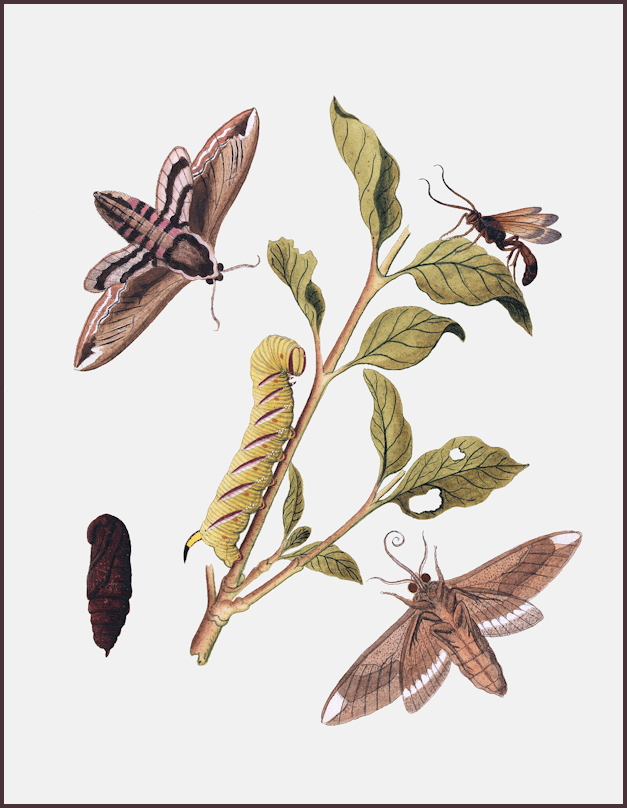

OVUM: Ovoid, pale green.

IMAGO: Hindwing with two dark submarginal bands. Proboscis approximately equal to length of body, and functional. Antenna of even thickness in both sexes and with a very weak terminal hook. Eye small and lashed. Abdomen with grey, white, pink or yellow and black 'rib' markings. Hindtibia with two pairs of spurs, the proximal much longer than the distal. Distinguished from all other Sphingidae (except Hyloicus) by the spined foretibia and lack of a pulvillus.

Genitalia. According to Hodges (1971), '...the male and female genitalia seem to offer fairly consistent points of difference to separate the species from those of other genera...The male genitalia are somewhat diverse; however...the saccus is relatively broad with the apex rounded; the saccular margin is heavily sclerotized, and the apex may be either bilobate or with a single lobe; the gnathos is broadly rounded to slightly spatulate; the uncus is broad at the base, tapering to a point, in some there is a ventral development; the phallus is unarmed, and one side tends to project beyond the opening for the vesica. In the female genitalia, the genital plate, consisting of the joined lamellae ante- and postvaginalis, often is a broad, heavily sclerotized unit; the ostium bursae is often centred on this plate; the base of the ductus bursae may be heavily sclerotized or not; the corpus bursae is membranous, and a slender, U-shaped signum with a series of short, pointed projections is present'.

LARVA: Head slightly narrowed above, almost round, never pyramidal; body cylindrical. Colour usually some shade of green; typically sphingiform, with seven oblique lateral streaks of white or white and a dark colour. In the final instar rarely granulose. Horn erect, slightly curved and glossy in the final instar.

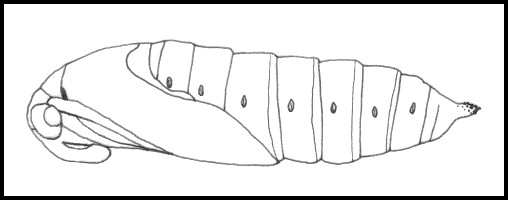

PUPA: Glossy reddish brown, with a small, free proboscis lying parallel to the body.

HOSTPLANT FAMILIES: Numerous, but mainly shrubs and trees of the Oleaceae, Rosaceae, Caprifoliaceae and Ericaceae.

UK: Privet hawkmoth, F: Sphinx du Troène, D: Ligusterschwärmer; Rainweidenschwärmer; Hartriegelschwärmer, RUS: Sirenevyi Brazhnik, S: Liguster-Svärmare, NL: Ligusterpijlstaart, CZ: Lišaj šeříkový, H: fagyalszender, E: esfinge del aligustre, PL: Zawisak tawulec, FIN: Sireenikiitäjä, I: sfinge del ligustro, HR: kalinin ljiljak, DK: Ligustersværmer, N: Ligustersvermer, EST: Sirelisuru.

Sphinx ligustri Linnaeus, 1758, Syst. Nat. (Edn 10) 1: 490.Type locality: Unspecified [Europe].

(Taxonomic notes. (i) de Freina & Witt (1984) synonymized subsp. nisseni and subsp. weryi with subsp. ligustri as there were insufficient features separating them. The resurrection of subsp. weryi by Eitschberger et al. (1992) was not accepted, and this subspecies was re-synonymized with subsp. ligustri.

(ii) The creation of subsp. eichleri for individuals from Kars Province, Turkey, cannot be justified. Many regional populations of subsp. ligustri show distinct characters, all of which fall within the normal range of variation found within the nominate subspecies.

(iii) Eitschberger & Lukhtanov (1996) described a new subspecies from Central Asia -- subsp. zolotuhini, stating that it can be "differentiated from the nominate form by its smaller size and the total absence of any brown tones, especially on the fore-wing uppersides. The area below the costal vein of the fore-wings is pure white, more or less strongly dusted with black scales. The fringes of the hindwings are black and not dark-brown as in the nominate form." This description matches that of Sphinx ligustri 'amurensis' Oberthür, 1886. Thus the question which should have been asked is not whether the populations from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are a new subspecies, but whether subsp. amurensis is indeed a subspecies and not a local form. Because of this, and as specimens from Shihezi and Ürümqi, China, are well within the normal variation found in European populations of Sphinx ligustri ligustri (Pittaway, pers. obs.), subsp. amurensis was synonymized with the nominate form by Kitching & Cadiou (2000).)

[Further details on this species, as well as photos of all stages, can be found on Lepiforum.]

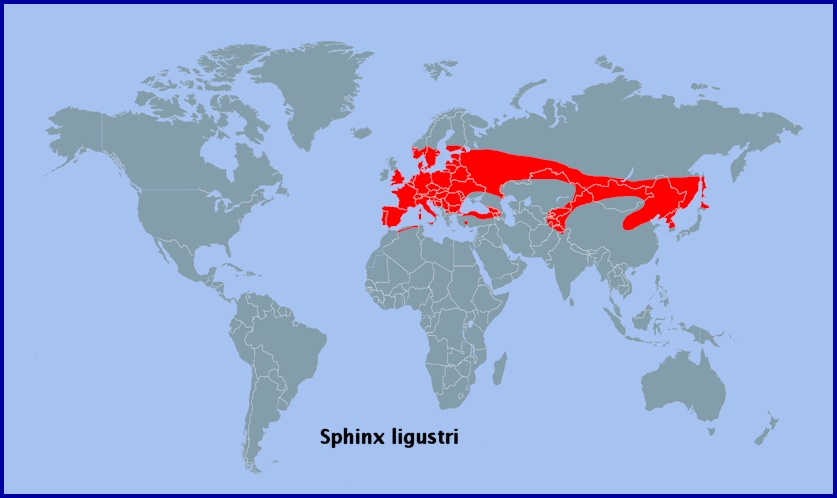

Holarctic; western Palaearctic region. Pleistocene refuge: Polycentric -- Pontomediterranen and Atlantomediterranean subsections of the Mediterranean refuge, as well as the Manchurian refuge.

Wingspan: 90--120mm. Difficult to confuse with any other European hawkmoth, although small, pale examples resemble the closely related North American Sphinx drupiferarum J. E. Smith, which is sometimes found in this region as an 'escapee'. Exhibits great variation: pink entirely replaced by grey (f. grisea Closs); pink replaced by white on the hindwings and abdomen only (f. albescens Tutt); abdominal 'ribs' yellow (f. lutescens Tutt). Numerous other minor variations occur in which pink, brown or black pigments are extensive. In the Hungarian Depression, a pale form occurs which was once thought to be a distinct species (Sphinx spiraeae Esper, [1800]), with the larva feeding on Spiraea; a similar pale form occurs in the drier regions of Central Asia (Eitschberger & Lukhtanov, 1996). There is no sexual dimorphism, although most females are generally larger than males.

In the male genitalia, uncus long, subcylindrical, gently curved, distally flattened, apex divided into two sharp points. Gnathos with a very long horizontal lobe divided into two long, slender, cylindrical, tapering processes. Valve broad, dorsally rounded, ventrally oblique, broadly rounded apically. Harpe ending in a broad, concave plate, the ventro-distal margin of which is turned up and slightly notched, whereas the oblique dorsal edge is irregularly dentate. Juxta rounded. Phallus ending in a short, broad, obtusely rounded process. In the female genitalia, ostial plate distinct from those of related species: the ostium is proximal; the middle of the post-ostial plate is flat, slightly concave laterally, convex mesially, smooth, bordered laterally by an oblique fold, which is often irregularly folded transversely.

An open-scrub and woodland-edge insect, showing a preference for limestone hills where Ligustrum vulgare is common, town suburbs with Ligustrum ovalifolium as a hedging plant, and river valleys rich in Fraxinus and Spiraea. Occurs up to 1500m in the Alps (Forster & Wohlfahrt, 1960) but only on the north-facing slopes of the Atlas Mountains in North Africa.

Rests by day on vertical surfaces such as fence posts, tree trunks and walls; rarely suspended from a twig. It is in such locations that mating pairs can be found 'tail to tail', although many separate in the afternoon and move two or three centimetres apart. Adults are active all night and can often be seen visiting privet (Ligustrum), honeysuckle (Lonicera) and many other sweet-scented flowers, with maximum activity about two hours after sunset. Both sexes are attracted to light.

Univoltine; June in northern Europe. Farther south bivoltine, April/May, and again in August as a partial to full second brood. June/July in the Altai Mountains. May/June on the lower Volga (Eversmann, 1844) and eastern Kazakhstan. In the southern Urals, from late May until early July (Nupponen & Fibiger, 2002).

OVUM: Pale green, elliptical, not very glossy (2.08 x 1.50mm). Up to 200 eggs are laid by each female on the underside of the leaves of the hostplant, usually singly, although two or three together are not uncommon. This stage lasts from 9--20 days, depending on temperature.

LARVA: Full-fed 90--100mm. Dimorphic: usually green; also a rare purple form.

On hatching, the larva measures approximately 5mm and is pale yellow with a long dark horn. The eggshell is not eaten. With feeding, the primary colour changes to luminescent green, speckled with yellow tubercles. After the first moult, lateral streaks appear as a series of dots, their final white and purple colours not developing until the third instar; the yellow tubercles disappear in the last. Variation is not great, but some larvae have darker than normal side stripes, often complemented by a second, lower purple one. Others may have two or more horns in series, each successively smaller. In some, the primary body colour of green may be replaced by shades of purple, but this form is very rare (Hornemann & Nässig, 2017).

Young larvae rest beneath the midrib of a leaf, but when fully grown they assume a typical upside-down sphinx-like attitude, clinging to a petiole or stem by their anal and last two prolegs, with the thoracic segments hunched. Specimens feeding on Ligustrum or Syringa are mostly to be found clinging to stripped shoots within two metres of the ground, as are also many of those on Fraxinus, with saplings being preferred to mature trees.

The larval stage lasts between four and seven weeks, after which the green colour is replaced dorsally by purplish brown before the larva descends in search of a suitable pupation site.

Commonest during August and September, but with significant numbers in July and October, depending on the season and locality.

Major Hostplants. Ligustrum vulgare, Ligustrum ovalifolium, Syringa vulgaris, Fraxinus excelsior, Fraxinus ornus and many species of Spiraea, the last mainly in central and south-eastern Europe. Zolotarenko, Petrova & Shiryaev (1978) record Viburnum opulus, Spiraea media, Spiraea salicifolia, Spiraea trilobata and Fraxinus viridis from western Siberia. In eastern Kazakhstan, Spiraea hypericifolia and Lonicera tatarica are favoured hosts (Toropov, Milko, Zhdanko & Evdoshenko, 2023).

Minor Hostplants. Ilex aquifolium (north-west Europe), Physocarpus opulifolius, Viburnum tinus, Viburnum lantana, Viburnum opulus, Euonymus europaeus, Cornus sanguinea, Symphoricarpos alba, Ribes, Rubus, Malus, Pyrus, Prunus avium, Sambucus nigra, Lonicera, Forsythia, Phillyrea, Olea europaea, Carpinus betulus, Sorbus aucuparia, Berberis vulgaris (Dutfield, 1748) and Nerium oleander (Roueast, 1883), although the latter is very doubtful. In some areas, Viburnum opulus may become a major host, and Leycesteria formosa (Himalayan honeysuckle), Jasminum nudiflorum (Winter jasmine), Buddleja davidii and Osmanthus x burkwoodii are sometimes utilized in British suburban gardens (Pittaway, pers. obs. 2015; 2021).

The largest larvae and fastest growth rates are often obtained utilizing lilac (Syringa vulgaris) as the main host (Rakhimov & Omonov, 2023). This may also effect the length of pupal diapause.

PUPA: 50--55mm. Rich, glossy brown. Pupation normally takes place in soft, loamy soil up to 10cm deep, in a hollowed-out chamber lined with a few strands of silk. The overwintering stage.

Ichneumonidae: Amblyjoppa fuscipennis (Wesmael, 1845), Apechthis compunctor (Linnaeus, 1758), Apechthis rufata (Gmelin, 1790), Callajoppa cirrogaster (Schrank, 1781), Callajoppa exaltatoria (Panzer, 1804), Goedartia alboguttata (Gravenhorst, 1829), Ichneumon insidiosus Wesmael, 1845, Pimpla turionellae (Linnaeus, 1758), Protichneumon fusorius (Linnaeus, 1761), Protichneumon pisorius (Linnaeus, 1758), Therion circumflexum (Linnaeus, 1758); Tachinidae: Baumhaueria goniaeformis (Meigen, 1824), Compsilura concinnata (Meigen, 1824), Drino (Zygobothria) atropivora (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830), Exorista larvarum (Linnaeus, 1758), Exorista sorbillans (Wiedemann, 1830), Frontina laeta (Meigen, 1824), Hubneria affinis (Fallén, 1810), Isosturmia picta (Baranov, 1932), Masicera sphingivora (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830), Nilea hortulana (Meigen, 1824), Phryxe erythrostoma (Hartig, 1838), Phryxe nemea (Meigen, 1824), Phryxe vulgaris (Fallén, 1810), Winthemia cruentata (Rondani, 1859).

Albin (1720) describes and illustrates a parasitoid of this species which appears to be Protichneumon pisorius.

Most of temperate Europe, including all of Spain and Portugal (Pérez De-Gregorio et al., 2001; Lara Ruiz, 2011; Fernández Vidal, 2016), Sicily (Mariani, 1939; Parenzan, 1995; Corso, 2011), Corsica (Philippe Geniez, iNaturalist 2011) and Sardinia (Marini & Trentini, 1986; Parenzan, 1995; Pier Francesco Murgia, iNaturalist 2019; Andrea Stangoni, iNaturalist 2022) eastwards to the Ural Mountains and lower Volga (Eversmann, 1844), Moldova (Tugulea & Tugulea, 2020), the Ukraine (Khalaim, 2022), western Siberia (Knyazev, 2020) as far north as Novosibirsk (Zolotarenko, Petrova & Shiryaev, 1978), the Altai Mountains (Izerskiy, 1999) and western China (western Xinjiang Province (Pittaway & Kitching, 2000)). From the Altai it pushes southwards into eastern and southern Kazakhstan (Dubatolov, [1999]; Toropov, Milko, Zhdanko & Evdoshenko, 2023), the Chatkal Mountains of Kyrgyzstan (Eitschberger & Lukhtanov, 1996; Korb, 2018; Toropov, Milko, Zhdanko & Evdoshenko, 2023), Uzbekistan (Toropov, Milko, Zhdanko & Evdoshenko, 2023; Omonov, Rahimov, Askarova & Khomidova, 2023; Andreas Manz, iNaturalist 2023; Omonov et al., 2025), northern Afghanistan (Danner, Eitschberger & Surholt, 1998), possibly northern Pakistan (Humairah Hanif et al., 2016), and maybe northwestern India (Smetacek, 1994).

In Europe its distribution extends south and southeastwards to eastern Turkey (de Freina, 1979; Danner, Eitschberger & Surholt, 1998; Okyar, 2012; Koçak & Kemal, 2018), Armenia (Dubatolov, [1999]; Didmanidze, Petrov & Zolotuhin, 2013; Wąsala & Zamorski, 2015), the Republic of Georgia (Didmanidze, Petrov & Zolotuhin, 2013), Daghestan (Abdurahmanov, 1999), Azerbaijan (Didmanidze, Petrov & Zolotuhin, 2013; Snegovaya & Petrov, 2021) and northern Iran (Lehmann & Zahiri, 2011), northern Algeria and northern Tunisia (Rothschild & Jordan, 1903; Oberthür, 1916; Rougeot & Viette, 1978). Common in western Europe but rarer farther east. Although still quite numerous in northern Turkey (de Freina, 1979; Okyar, 2012), it is absent from parts of the Balkan Peninsula and northern Scandinavia, but present in Croatia (Koren & aić, 2023), the Republic of North Macedonia (Krpač et al., 2019), Bulgaria (Hristova & Beshkov, 2016) and Romania (Linnell, Kaltenborn, Bredin & Gjershaug, 2016). Recorded only as far north as Kobra (Tatarinov, Sedykh & Dolgin, 2003) and Karelia (Kutenkova, Gorbach, Polevoi & Humala, 2015) in european Russia. A partial migrant north-westwards.

Recorded from the Azores in the past, but now considered extinct there (Vieira, 1997).

Extra-limital range. From the Altai Mountains of Russia east across southern Siberia (Izerskiy, 1999), central-northern China (Shaanxi Prov. (Pittaway & Kitching, 2000)), Mongolia (Yakovlev, Gus'kova, Doroshkin & Titov, 2015; Yakovlev & Doroshkin, 2017; Knyazev, Makhov, Matov & Yakovlev; 2020; Makhov, Matov & Lukhanov, 2024), north-east China and the Russian Far East (Izerskiy, 1999; Streltzov, Osipov & Malikova, 2003) to the Kurile Islands and northern Japan (Hokkaido).

None. Sphinx constricta Butler, 1885, which is distributed throughout southern and central Japan (including the southern tip of Hokkaido), was formerly regarded as a subspecies of Sphinx ligustri but is now considered by Kishida (1987) to be a distinct species.

Return to species list

Return to species list